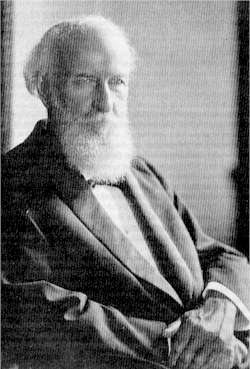

Joseph Kidd FRCSE (15 February 1824 – 20 August 1918) was an Irish orthodox physician who converted to homeopathy and later became the homeopathic physician to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli 1st Earl of Beaconsfield. He was a student of Paul Francois Curie at the Hahnemann Hospital at 39 Bloomsbury Square,

Joseph Kidd FRCSE (15 February 1824 – 20 August 1918) was an Irish orthodox physician who converted to homeopathy and later became the homeopathic physician to Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli 1st Earl of Beaconsfield. He was a student of Paul Francois Curie at the Hahnemann Hospital at 39 Bloomsbury Square,

Joseph Kidd was born in Limerick, Ireland, on 15 February 1824, one of eighteen children of Thomas Keane Kidd, a corn merchant, and his wife Rebecca, a Quaker. On his mother’s initiative Kidd was sent to a Quaker school where he cultivated a particular interest in the classics.

Kidd decided on a medical career and in 1841 became apprenticed to a Limerick physician, Dr O’Shaughnessy (very likely James O’Shaughnessy MRCS c.1810-1903). Across the street was another physician who had an apprentice named Richard Quain who acquired a great reputation as an allopath in London in later years.

In 1842 Kidd went to Dublin where he studied with one of the first orthodox Irish physicians to convert to homeopathy, William Walter. There Kidd gained experience in dispensing, surgery, and home visiting. During his free hours each day Kidd studied for the MRCS of England, passing the exam in 1846.

At the same time Kidd applied for a vacancy at the new Hahnemann Hospital in Bloomsbury Square that had been advertised in the London Times, though he was not yet then qualified to practice. He triumphed over sixteen qualified men who had applied for the appointment and was elected house surgeon at the Hahnemann Hospital where he worked under Paul Francois Curie, grandfather of Pierre Curie.

Almost immediately in 1847 the Irish Potato Famine broke out. Kidd was selected to go to Ireland to assist by the English Homeopathic Society. He was dispatched to Bantry Bay, close to two of the main centres of suffering, Schull and Skibbereen.

Kidd wrote an account of his experiences during the Famine. He was eager to demonstrate that homeopathy would be effective in the most adverse of conditions where allopathy was ineffective. The results, as he noted, were pronounced:

In 67 days he saw 192 patients. He visited them at home and after one week he had as many patients as there was time to visit each day, and the pace carried on. He was only 25 years old and inexperienced. Yet he noticed how the available food, mainly Indian corn imported by the British as aid, was not suitable to help the sick recover so he managed to obtain rice and other better foods from a London voluntary relief agency set up by an alliance of Jews and Quakers.

“That those under homeopathic treatment, circumstanced as they were in general without proper food or drink, should have succeeded as well as the inmates of the hospital of the same town (taken from precisely the same class of people), with the advantages of proper ventilation, attendance, nourishment etc. would have been most gratifying; but that the rate of mortality under the homeopathic system should have been so decidedly in favour of our grand principle, is a circumstance, it may be hoped, which can scarcely fail to attract the attendance of even the most sceptical.”

Returning to London, Kidd became a member of the British Homoeopathic Society in 1847 and established successful practices in Blackheath and the City of London. Over the next few years he attracted patients from all classes and all over the country, setting up another practice in the West End. By 1853 he had graduated MD from King’s College Aberdeen.

Kidd’s most distinguished patient was the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield. The first mention made of Kidd by Disraeli was a diary entry in September 1877:

“The only drawback is my health. I really don’t see how I can meet Parliament unless some change takes place. It would be impossible for me to address a public assembly. There is no one to consult. Gull, in whom I have little confidence, is still far away, and Dr Kidd, whom all my friends wish me to consult, and who of course like all untried men is a magician, won’t be in town until the middle of October, and is such a swell that, I believe, he only receives, and does not pay visits – convenient for a Prime Minister!”

By November Disraeli had taken the advice of his friends, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh, who appears to have also been under Kidd’s care. As Disraeli recorded on 7 November 1877:

“Today I saw Dr Kidd who cured the Chancellor. I like him much. He examined me as if I were a recruit – but reports no organic deficiency. My main complaint is bronchial asthma, more distressing than bronchitis, but curable where bronchitis is not, and I am to be cured – and very soon!”

Kidd clearly made an impression on Disraeli who continued in his diary:

“I had made up my mind never to breathe a word as to my progress or the reverse, until I had given my new man a fair and real trial: but as you press me I can refuse nothing. I will tell you that I entertain the highest opinion of Dr Kidd, and that all the medical men I have known, and I have seen the highest, seem much inferior to him, in quickness of observation, and perception, and reasonableness, and at the same time originality, of his measures. I am told his practice is immense, and especially in chest and bronchial complaints. The difficulty is in seeing him, as he does not like to leave his house.”

According to Dana Ullman, Kidd normally only saw patients in his home office, but he made a rare exception for Disraeli. In July 1878, Kidd was called to Berlin to attend to Disraeli who was attending the Congress of European powers hosted by German chancellor Bismarck.

In 1881, during the final days of Disraeli’s life, Queen Victoria urged him to see Richard Quain, an allopathic physician. Ordinarily, the enmity of allopaths towards homeopaths would have precluded such cooperation. However, given the patient, and the long acquaintance of Kidd and Quain from their days as medical students in Limerick, alongside a third physician, the allopath John Mitchell Bruce, they attended Disraeli together until his passing.

In his account of treating Disraeli, Kidd subsequently revealed a diagnosis of Bright’s disease, in addition to asthma, which had given Disraeli great trouble, as he would take no exercise. Kidd recorded that he prescribed Ipecacuanha, Kali iodatum, Arsenicum, and lamp baths, observing that the Prime Minister “had much more faith in wise general hygienic and dietetic treatment than in medicines.”

During the next two decades Kidd continued with his successful London practice. One of his patients was the influential preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon. He also remained a member of the Medical Council of the London Homeopathic Hospital and was Consulting Physician at the Lower Tottenham Infirmary for Woman and Children.

In 1850 Kidd married Sophia McKern, a childhood friend from Limerick whose brother, Thomas Mackern, was also a homeopath. With Sophia he had eight children. Five of these followed him into the medical profession, including the eldest, Dr. Percy Marmaduke Kidd, and a daughter, Dr. Mary Kidd, secretary of the Maternity and Child Welfare Group of the Society of Medical Officers of Health.

Sophia died in 1872, and in 1875 Kidd married Frances Octavia Rouse, with whom he had another seven children.

He continued working until he was almost 90 years old and died aged 94 on 20 August 1918, in Hastings, Sussex. On Kidd’s death The Lancet provided an unusually positive and lengthy obituary, recording how:

“He always held fast to the opinion that there is a truth contained in the doctrine of homeopathy which at times supplies a clue to the treatment of obscure cases.”

“…From an early period he adopted the practice of prescribing only one drug at a time so as to be better able to study the action of individual remedies. A large part of his success must be attributed to his careful survey of small details. This habit undoubtedly helped him to create the confidence reposed in him by his patients.”

“He trusted little to notes but he seldom forgot a name or an important fact. He retained his mental and bodily powers far beyond the ordinary limits of age, and he only retired from practice in his ninetieth year.”

Select Publications:

- Homoeopathy in Acute Diseases: Narrative of a Mission to Ireland (1849)

- Directions for the Homeopathic Treatment of Cholera (1866)

- The Laws of Therapeutics or the Science and Art of Medicine: A Sketch (1878)

- Heart Disease and the Nauheim Treatment (1897)

Of interest:

Percy Marmaduke Kidd 1851 — 1942 was a British doctor and the oldest of the eight children of Joseph Kidd and his first wife Sophia McKern. Like his father, Percy Kidd became an eminent London doctor. Two of his four brothers – Walter Aubrey Kidd (1852 – 1929) and Leonard Joseph Kidd (1858 – 1926), along with his sister Beatrice Mary Kidd (1876 – 1957), also became doctors; a third brother died young, while still training to become one.

Ronald Hubert Kidd (1889 – 1942) was a civil rights campaigner and a grandson of Joseph Kidd. He founded the National Council for Civil Liberties, now known as Liberty.

Another grandson was the cricketer, Eric Leslie Kidd, Director of Guinness Ltd.

I wonder if there is extant a catalogue of the sale of Dr Kidd’s effects. I have a clock which family lore says was purchased at the sale. I also have a nice Jaques portable chess set on which an ancestor is supposed to have played chess with Disraeli when commuting by train into London. Whilst there seems no chance of establishing the latter, it might I suppose be possible to authenticate the former were such a sale record to exist.

My sister is the enthusiastic genealogist, and I have just discovered a couple of useful references for her. Whilst searching, it occurred to me to look again for information on Disraeli’s doctor.

Any comments would be much appreciated.

M.J.P.