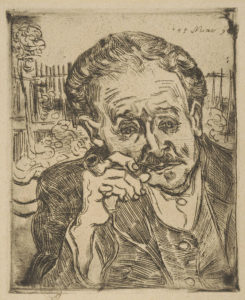

Vincent van Gogh, Man with a Pipe (Portrait of Dr. Paul Gachet, 15 May 1890). Image credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Paul Ferdinand Gachet M.D. (30 July 1828 – 9 January 1909) was a French disciple of Samuel Hahnemann and he was a student of homeopath Jean Jacques Molin, and a colleague of Georges de Bellio. He also knew French homeopath Julien de Durand de Monsetrol who he met in 1854.

Gachet was the homeopathic practitioner of Paul Cezanne, Joseph Conrad, Theophile Gautier, Vincent van Gogh, Camille Pissarro, Edouard Manet, Pierre Auguste Renoir and many others, and he was a friend of Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet.

He bought a house at Auvers sur Oise and, in his studio there, became an enthusiastic engraver, partly as a consequence of his earlier contacts with Daumier, Charles Meryon and Rodolphe Bresdin, artists whose styles were reflected in his own.

It was in this studio that several of the Impressionists took up etching: Paul Cezanne produced there an etching of Guillaumin, as well as painting a number of flower pieces arranged in Delft vases for him by the doctor’s wife. On the recommendation of Camille Pissarro, Gachet took Vincent van Gogh into his house.

Vincent van Gogh arrived in Auvers sur Oise on May 20, 1890, hoping to find a resolution to the physical and psychological problems that plagued him. The artist was optimistic that the doctor would diagnose his baffling illness, but he committed suicide just two months later after a burst of artistic energy which produced a canvas a day.

Gachet’s great collection of paintings by all the major figures of the movement was given to the state by his son and is now in the Musée d’Orsay.

Paul Ferdinand Gachet who worked in Paris for 50 years specialized in mental diseases of women and children, was art amateur and friend of many impressionists among them Pissaro who recommended Vincent van Gogh to him.

While Gachet followed a diverse range of medical pathways, such as electrotheraphy, phytotherapy and many others he obviously possessed a distinct knowledge of homeopathy, even though homeopathy did not figure on his cards, letters and advertisements.

On December 6th and 7th, 2004, we were able to analyze the two pharmacies owned by Gachet and housed since 1990 in the museum for history of medicine in Paris, Rene Descartes University. Both carry his name on it: one is a small travel kit containing 12 remedies, the other a larger box containing 98 remedies in glass tubes sealed with cork.

The potency and the name of the drug are handwritten or printed on top of the corks. Only few were unreadable. The remedies of the small travel kit were acon, ars, arn, bell, carb-v, ipecac, merc-sol, nux-v, phos, puls, and an unidentified tube, mostly in C3 potency.

The larger pharmacy contained remedies from led to stann, with some unidentified and some rare remedies, such as merc-cyan, mur-ac, rizin, sabin among others. Most were in C6, but some also in C12, C18, C24 up to C30 potency. Curiously there were often several drugs of the same potency as opium, phos, samb, staph.

The discovery of Gachet’s homeopathic pharmacies, which certainly are only a part of the homeopathic remedies he used, because it only runs from L to S, gives insight in the way how a physician who at least sympathized with homeopathic treatment worked at the end of the 19th century.

We suggest that his original pharmacy must have contained 400-500 tubes in 4-5 boxes. From the variety of drugs, the obvious use of the pharmacies with different filling levels, different tubes and different fonts on the cork we conclude that the user must have had a good knowledge and a broad and subtle use of homeopathic drugs.

All sorts of mercury salts may suggest the treatment of syphilis, while remedies known to be used against cholera as well as hysterical women’s remedies indicate Gachet’s intentions to cure homeopathically in his main subjects.

It is reported that Gachet treated many impressionists, such as Camille Pissarro, Edouard Manet, Paul Cezanne and Pierre Auguste Renoir….

Vincent, 37 years old and suffering from depression, was encouraged to travel to Auvers from Arles by his brother Théo and Camille Pissaro. Vincent was to seek out a homeopathic physician, one Paul Gachet. Supposedly, the doctor suffered from the same nervous disorder as Vincent (possibly epilepsy compounded by bipolar disorder). Of the doctor, Vincent says he has, “found a perfect friend in Dr. Gachet, something like another brother.” The doctor tells him to put his ailment out of his mind and concentrate entirely on his painting.

In his youth, Gachet hung out in Paris cafes with Courbet, Edouard Manet and Charles Pierre Baudelaire. In 1872 he moved to the village of Auvers sur Oise, where his neighbor Camille Pissarro introduced him to Paul Cezanne and Armand Guillamin. He met Edouard Manet, Pierre Auguste Renoir and scores of others less known today.

Gachet was there when Paul Cezanne sneered at Edouard Manet‘s masterful Olympia and dashed off his own version, A Modern Olympia (Sketch), saying it was “mere child’s play.” Gachet snatched it up and later lent it to the 1874 Impressionist exhibition, entering history as one of the first fans of the great proto-modernist.

Gachet tended Vincent van Gogh in his last days, and even made several death bed drawings of the artist. In the 1980s art boom, it was Vincent van Gogh‘s Portrait of Dr. Gachet that sold at auction for a record $82.5 million. Who says history doesn’t have a sense of poetry?

But the tale doesn’t end with Gachet’s death in 1909. For the next 40 years, the Gachet collection was kept hidden away by his daughter Marguerite (1869-1949) and son Paul (1873-1962), a reclusive scholar who spent most of his adult life writing a history of Vincent van Gogh‘s 70 super-productive days at Auvers.

After Marguerite passed away, the collection eventually ended up in the Musée d’Orsay.

But there were further complications. Both Gachet père et fils were ardent amateur painters and copyists. For a time, the elder Gachet (who showed his paintings as Paul van Ryssel) worked side by side with Camille Pissarro, Guillaumin and Paul Cezanne in the attic of his Auvers house.

In 1956, Gachet fils boasted of his close study of works in the family collection, “copying them so well that I dare write here, and for the first time, that without classes or lessons, I am at heart and soul, Paul Cezanne‘s student.”

What’s more, the good doctor had early on conceived a plan to publish a book on Vincent van Gogh, and enlisted several people to make copies of his work — notably Blanche Derousse, the seamstress-daughter of a neighbor. She is responsible, for instance, for a copy of Vincent van Gogh‘s 1889 Self-Portrait – in watercolor.

As a result, no one is quite sure who made some of the Gachet pictures. Especially since Vincent van Gogh seems to have made a few copies of his work himself. Even more interesting is the degree of difficulty, in our postmodernist age, of establishing aesthetic superiority for some of these originals.

The exhibition, which premiered at the Grand Palais in Paris and will travel to the Vincent van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, contains some 130 items in all. It has to be the most free-wheeling show the Met has ever mounted. In addition to a handful of historical novelties like Vincent van Gogh‘s palette, a still life pot that Paul Cezanne painted and even the famous white sailor hat Gachet wore in that multimillion-dollar portrait, it features works in questionable condition, of uncertain quality and dubious authenticity. It looks like this stuff was stashed away for 50 years.

And everywhere, original is posted next to contemporaneous copy. Sometimes the copy is wretched. Sometimes it’s scary close.

That’s what makes the show so fascinating. There’s way too many versions of a Cezanne green apple. There’s a wall of 14 watercolor copies of Vincent van Gogh works by Derousse that have to be seen to be believed. There’s a Pierre Auguste Renoir portrait of a girl with a patch of skin on her nose that looks like it was painted by Lucien Freud. There’s Camille Pissarros and Guillamins that look crappy — but that’s the way their stuff is half the time. And there’s a great 1879 Cezanne still life, called The Accessories of Cezanne, from the period when the artist still favored gummy paint texture and lots of black. It was done on cardboard and probably would have fallen apart if Gachet hadn’t been such a fan.

Leave A Comment