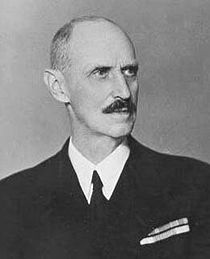

Haakon VII (Christian Frederik Carl Georg Valdemar Axel) (3 August 1872 – 21 September 1957), known as Prince Carl of Denmark until 1905, was the first king of Norway after the 1905 dissolution of the personal union with Sweden.

Haakon VII (Christian Frederik Carl Georg Valdemar Axel) (3 August 1872 – 21 September 1957), known as Prince Carl of Denmark until 1905, was the first king of Norway after the 1905 dissolution of the personal union with Sweden.

Haakon was a patient (Peter Morrell, A History of Homeopathy in Britain, (Staffordshire University)) of Sir John Weir, and Haakon awarded Weir the Knight Grand Cross of St. Olav in 1938 (Dana Ullman, The Homeopathic Revolution: Why Famous People and Cultural Heroes Choose Homeopathy. (North Atlantic Books, 2007). Page 363).

Haakon was the son in law of Edward VII,

Known in his youth as Prince Carl of Denmark (namesake of his maternal grandfather the King of Norway etc), he was the second son of the future Frederick VIII of Denmark and a younger brother of the future Christian X of Denmark. He was a paternal grandson of Christian IX of Denmark (during whose reign he was prince of Denmark) and a maternal grandson of Charles XV of Sweden, who was also king of Norway (as Charles IV).

He personally became king of Norway before his father and brother became kings of Denmark. During his reign, he saw his father, his brother and his nephew Frederick IX ascend the throne of Denmark, respectively in 1906, 1912 and 1947.

Prince Carl was born at Charlottenlund Palace near Copenhagen. He belonged to the Schleswig Holstein Sonderburg Glucksburg branch of the House of Oldenburg. The House of Oldenburg had been the Danish royal family since 1448, and between 1536-1814, also ruled Norway when it was part of the Kingdom of Denmark Norway. The house was originally from northern Germany, where also the Glucksburg (Lyksborg) branch held their small fief.

The family had permanent links with Norway already beginning from late Middle Ages, and also several of his paternal ancestors had been kings of independent Norway (Haakon V of Norway, Christian I of Norway, Frederick I, Christian III, Frederick II, Christian IV, as well as Frederick III of Norway who integrated Norway into the Oldenburg state with Denmark, Slesvig and Holstein, after which it was not independent until 1814). Christian Frederick, who was King of Norway briefly in 1814, the first king of the Norwegian 1814 constitution and struggle for independence, was his great granduncle.

Prince Carl was raised in the royal household in Copenhagen and educated at Royal Danish Naval Academy from which he graduated near the bottom of his class. He was a key witness in the scandal following the suicide of Kai Simonsen.

At Buckingham Palace on 22 July 1896, Prince Carl married his first cousin Princess Maud of Wales, youngest daughter of the future Edward VII of the United Kingdom and his wife, Alexandra of Denmark, daughter of King Christian IX of Denmark and Princess Louise of Hesse Kassel (or Hesse Cassel). Their son, Prince Alexander, the future Crown Prince Olav and finally Olav V of Norway, was born on 2 July 1903.After the Union between Sweden and Norway was dissolved in 1905, a committee of the Norwegian government identified several members of European royalty as candidates for Norway’s first king of its own in several centuries. Gradually, Prince Carl became the leading candidate, largely due to the fact that he was descended from independent Norwegian kings. He also had a son (and hence an heir to the throne), and Princess Maud’s ties to the British royal family were viewed as advantageous to the newly independent Norwegian nation.

The democratically minded Carl, aware that Norway was still debating whether to retain its monarchy or to switch to a republican system of government, was flattered by the Norwegian government’s overtures, but declined to accept the offer without a referendum to show whether monarchy was truly the choice of the Norwegian people.

After the referendum overwhelmingly confirmed by 79 percent majority (259,563 votes for and 69,264 against) that Norwegians desired to retain a monarchy, Prince Carl was formally offered the throne of Norway by the Storting (parliament) and elected on 18 November 1905.

When Carl accepted the offer that same evening (after the approval of his grandfather Christian IX of Denmark), he immediately endeared himself to his adopted country by taking the Old Norse name of Haakon, a name used by previous kings of Norway. In so doing, he succeeded his grand uncle, Oscar II of Sweden, who had abdicated the Norwegian throne in October following the agreement between Sweden and Norway on the terms of the separation of the union. The coronation of Haakon and Maud took place in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim on 22 June 1906.

Norway was invaded by the naval and air forces of Nazi Germany during the early hours of 9 April 1940. The German naval detachment sent to capture Oslo was challenged at Oscarsborg Fortress. The fortress fired at the invaders, causing damage to the pocket battleship Lützow and the sinking of the heavy cruiser Blücher, with heavy German losses that included many of the armed forces, Gestapo agents, and administrative personnel who were to have occupied the Norwegian capital.

These events led to the withdrawal of the rest of the German flotilla, preventing the invaders from occupying Oslo at dawn as had been intended in the order of battle. The German occupation forces’ delay in arrival in Oslo, along with swift action from the President of the Storting C. J Hambro, in turn created the opportunity for the Norwegian royal family, the cabinet, and most of the 150 members of the Storting (parliament) to make a hasty departure from the capital by special train.

The Storting first convened at Hamar the same afternoon, but with the rapid advance of German troops, the group moved on to Elverum. The assembled parliament unanimously enacted a resolution, the so-called Elverumsfullmakten (Elverum Authorization), granting the Cabinet full powers to protect the country until such time as the Storting could meet again.

The next day, German minister Curt Brauer demanded a meeting with Haakon. The German diplomat called on the Norwegians to cease their resistance and stated Hitler‘s demand that the king appoint Nazi sympathizer Vidkun Quisling as prime minister of what would be a German puppet government.

Brauer suggested that Haakon follow the example of the Danish government and his brother, Christian X, which had surrendered almost immediately after the previous day’s invasion, and threatened Norway with harsh conditions if it didn’t surrender. Haakon told Brauer that he could not make such a decision himself, but only on the advice of the government. Although the Constitution of Norway nominally gives the king the final responsibility for making such a decision, it is a well established convention that the king does not make any major political decisions on his own initiative.

In an emotional meeting with the Cabinet in Nybergsund, the king reported the German ultimatum to his cabinet. Although he could not make the decision himself, he knew he could use his moral authority to influence it. Accordingly, Haakon told the Cabinet:

- I am deeply affected by the responsibility laid on me if the German demand is rejected. The responsibility for the calamities that will befall people and country is indeed so grave that I dread to take it. It rests with the government to decide, but my position is clear.

- For my part I cannot accept the German demands. It would conflict with all that I have considered to be my duty as King of Norway since I came to this country nearly thirty five years ago.

Haakon went on to say that he could not appoint any government headed by Quisling because he knew neither the people nor the Storting had confidence in him. However, if the Cabinet felt otherwise, the king said he would abdicate so as not to stand in the way of the government’s decision.

Inspired by Haakon’s stand, the government announced its refusal to accept the German terms to the German emissary by telephone. In a radio broadcast that evening, the government and king’s refusal to the German ultimatum were announced to the Norwegian people. The government indicated that they would resist the German attack as long as possible, and expressed their confidence that Norwegians would lend their support to the cause.

The following morning, 11 April 1940, bomber aircraft of the Luftwaffe attacked Nybergsund, destroying the small town where the Norwegian government was staying in an attempt to wipe out Norway’s unyielding king and government. The king and his ministers took refuge in the snow covered woods and escaped harm, continuing farther north through the rugged Norwegian mountains toward Molde on Norway’s northwestern coast.

As the British forces in the area lost ground under Luftwaffe bombardment, the king and his party were taken aboard the British cruiser HMS Glasgow and conveyed by sea to Tromsø where a provisional capital was established on 1 May. Haakon and Crown Prince Olav took up residence in a forest cabin in Målselvdalen valley in inner Troms county where they would stay until the evacuation to the United Kingdom.

While residing in Troms the two were protected by local rifle association members armed with the ubiquitous Krag-Jørgensen rifle.

The Allies had a fairly secure hold over northern Norway until late May, but as the Allies’ position in the Battle of France rapidly deteriorated, the Allied forces in northern Norway were badly needed elsewhere and were withdrawn.

The beleaguered and demoralized Norwegian government was evacuated from Tromsø on 7 June aboard HMS Devonshire; and after a 34-knot (63 km/h) dash, under cover of HMS Glorious, HMS Acasta, and HMS Ardent, safely arrived in London. Haakon and his cabinet set up a Norwegian government in exile in the British capital.

Taking up residence at Rotherhithe in London, Haakon was an important national symbol in the Norwegian resistance. Between March 1942 and the end of the war in June 1945 the King and his son, Crown Prince Olav, lived at Foliejon Park in Winkfield, near Windsor.

Meanwhile, Hitler had appointed Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar for Norway. On Hitler’s orders, Terboven attempted to coerce the Storting to depose the king; parliament declined, citing constitutional principles. A subsequent ultimatum was made by the Germans under threat of interning all Norwegians of military age in German concentration camps.

With this threat looming, the Norwegian parliament’s representatives in Oslo wrote to their monarch on 27 June, asking him to abdicate. The king, politely replying that the Storting had acted under duress, declined the request. After one further German attempt in September to force the Storting to depose Haakon failed, Terboven finally decreed that the royal family had “forfeited their right to return” and dissolved the democratic political parties.

During Norway’s five years under German control, many Norwegians surreptitiously wore clothing or jewelry made from coins bearing Haakon’s “H7” monogram as symbols of resistance to the German occupation and of solidarity with their exiled king and government, just as many people in Denmark wore his brother’s monogram on a pin. The king’s monogram was also painted and otherwise reproduced on various surfaces as a show of resistance to the occupation.

After the end of the war, Haakon and the Norwegian royal family returned to Norway aboard the cruiser HMS Norfolk, arriving to cheering crowds in Oslo on 7 June 1945.

King Haakon VII fell in his bathroom at the estate at Bygdøy in July 1955. This fall, which occurred just a month before his eighty third birthday, broke the king’s thighbone and, although there were few other complications resulting from the fall, the king was left confined to a wheelchair. The once active king was said to have been depressed by his resulting helplessness and began to lose his customary involvement and interest in current events.

With Haakon’s loss of mobility and, as the king’s health deteriorated further in the summer of 1957, Crown Prince Olav appeared on behalf of his father on ceremonial occasions and taking a more active role in state affairs.

At Haakon’s death in 1957, the crown prince succeeded as Olav V.

Today, King Haakon is regarded by many as one of the greatest Norwegian leaders of the pre-war period, managing to hold his young and fragile country together in unstable political conditions. In 1927 he said “Jeg er også kommunistenes konge”, or “I am also the communists’ king”. His loyalty to democracy proved to be crucial for Norway’s political situation during and after World War II.

Leave A Comment