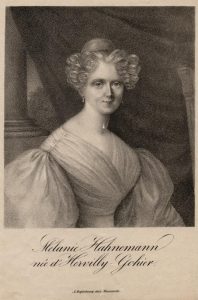

Marie Mélanie d’Hervilly Gohier Hahnemann (2 February 1800 – 27 May 1878) was a French homeopathic physician and the first qualified medical woman in the world.

In January 1835, Mélanie married Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy. Mélanie became Hahnemann’s apprentice and subsequently his most trusted assistant.

After Hahnemann’s death in 1843 Mélanie continued to practice homeopathy in Paris. She also safeguarded Hahnemann’s medical case books, and his revised manuscript for what would become the sixth and final edition of the Organon.

Mélanie was born into a French aristocratic family, her father was the Comte Joseph d’Hervilly.

As a child Mélanie had developed a questioning disposition and displayed an early proclivity towards medicine. Later in life she recalled how “I had extraordinary inspirations when I was near a sick person.”

At the age of fifteen, Mélanie was sent away by her father to reside in Paris with her painting tutor, Guillaume Guillon-Lethière. Inspired by Lethière and his circle, Mélanie became a successful artist in Paris during the 1820s, displaying several of her works at the Louvre and winning a gold medal at the 1824 salon.

As a child of the French Revolution and a young adult during the era of Romanticism, Mélanie was imbued with the creative and radical spirit of the age. In addition to painting she also composed poetry and in 1825 she published her only surviving long poem, L’Hirondelle Athénienne (The Athenian Swallow). This was sold to raise funds in support of Greek independence.

Around this time Mélanie met the Republican politician and president of the Directory, Louis-Jérôme Gohier . A platonic friendship evolved that would result in Gohier bequeathing Mélanie his name and his fortune on his death in May 1830.

Source: Smithsonian

Mélanie’s circle of friends and mentors throughout this period included some of the most notable figures of the Revolutionary era, including the Catholic priest Henri Jean-Baptiste Grégoire, known as the Abbé Grégoire (1750 – 1831), the radical politician, celebrated poet and playwright François Guillaume Jean Stanislaus Andrieux (1759 – 1833), whose final poem, Hymne à Sainte Mélanie, was dedicated to her, and the poet and playwright Louis Jean Népomucène Lemercier (1770 – 1840).

The deaths of all of these important figures in her life coincided with Mélanie’s first introduction to homeopathy. English physician Frederick Hervey Foster Quin (1799 – 1879) had visited Paris in 1831 and 1832, at the height of the Second European cholera pandemic and had earned a reputation for treating cholera victims.

By 1834, Mélanie’s health had deteriorated. She obtained a copy of the 1829 French translation of the fourth edition of Hahnemann’s Organon and promptly visited Hahnemann in Köthen seeking cure. A few months later, in January 1835, they married with Mélanie renouncing her claim to Hahnemann’s wealth as a demonstration of her devotion.

In June 1835, Hahnemann and Mélanie left Köthen for Paris where Hahnemann was granted permission to practice in August, 1835.

Mélanie was deeply involved in his clinical work. Genevan homeopath Dr. Charles Peschier, Secretary of La Société Homoeopathique Gallicane (the Gallic Homeopathic Society), visited them shortly after their arrival and remarked on her medical acumen:

“Gifted in a very great degree she now applies all the force of her mind to the study of homeopathy and, possessed of a most excellent memory, she is able to narrate promptly to the learned physician the symptoms recorded in the Materia Medica corresponding to the disease. She has become capable of tabulating morbid symptoms with great exactitude; in the same manner that she has become the hand of Hahnemann she has also become his head…She receives the respect of all the homeopaths.”

By June 1836, Samuel Hahnemann wrote to a colleague that she was “now the keenest pupil, and has good knowledge of the homeopathic method of treatment.” However, he understood that Mélanie could not practice openly without qualifications and so requested Constantine Hering at the Pennsylvania Allentown Academy (The North American Academy of the Homeopathic Healing Art) confer a medical diploma on his wife. After lengthy deliberation, in 1840, Hering and his associates granted Mélanie a diploma, nine years before Elizabeth Blackwell and ten before the first American woman doctor, Lydia Folger Fowler, herself an eclectic physician who employed homeopathy in her practice.

Hahnemann died in Paris in July 1843, and was interred in Montmartre Cemetery in Mélanie’s family plot, alongside Lethiere and Gohier.

On his death, Hahnemann entrusted Mélanie with his clinic and his papers. These included his case notes and records of experimental workings, in addition to the annotated manuscript for his revised, sixth edition of the Organon. For the rest of her life Mélanie protected his memory, withholding the sixth edition manuscript from publication, as Hahnemann had requested, until the time was right. World events and her own circumstances meant this was not achieved in her own lifetime and Hahnemann’s sixth edition was not finally published in German until 1921, and in English the following year.

After Hahnemann’s death, Mélanie resumed practicing homeopathy in Paris and at Versailles, but she faced tremendous hostility and resentment from allopaths and homeopaths alike. In February 1847, she was brought up on charges and fined for illegal practice. Nevertheless, Mélanie continued to practice and, after the 1848 Revolution, found influential political friends once more. She was finally granted a French medical license in 1872 by virtue of her American diploma.

In 1851, Sophie, the daughter of musicians Anton and Fanny Böhrer, came to live with Mélanie in Paris. Mélanie would later formally adopt Sophie as her own daughter.

Mélanie had planned to meet Hahnemann’s closest friend, Clemens Maria Franz Baron von Bönninghausen, at the Gallican homeopathic congress, held in Brussels on 24 September 1856. Forty homeopaths from France, Belgium, Holland, Russia, Germany and Algeria, attended this meeting. However, due to the intervention of French homeopaths, led by Léon Simon and Antoine Petroz, she was prevented from attending.

In 1857, Mélanie arranged for Sophie to marry Karl (Charles) Antoine Hubert Walburgis von Bönninghausen, a young homeopathic doctor and the son of Clemens von Bönninghausen. With Karl’s assistance, Mélanie set up what became a thriving practice in Paris, while still continuing her Versailles practice.

Following the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Karl and Sophie relocated to his family’s Westphalian estates where Karl resumed practice in Münster.

Mélanie remained in Paris and began prescribing again. On May 27, 1878, she died of pulmonary catarrh and was at last buried alongside Hahnemann in Montmartre.

In the editor’s preface to the 1922 English edition of Haehl’s biography of Hahnemann, John Henry Clarke and Charles Wheeler acknowledged Mélanie’s role in resettling Hahnemann in Paris and the resultant boom in homeopathy across Europe:

With all her faults and peculiarities, Madame Melanie Hahnemann’s action had this effect; and even given the impossible price she put on Hahnemann’s literary remains had this good result – it preserved them all intact until the one man in the world who ever could make proper use of them arrived – Dr. Richard Haehl himself! And it gave them into possession without price. Therefore we think that Madame Melanie Hahnemann has a not unworthy place in the history of Hahnemann and his Homoeopathy.

And on this day 8th March – International Women’s Day this lady must be honoured for her contributions!!

Completely agree Lin. Thank you for your comment.