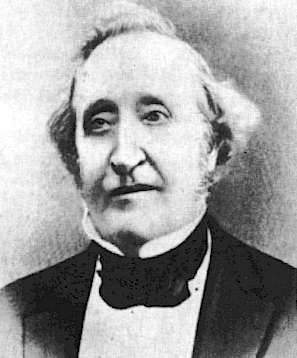

Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte M.D. (6 October 1811 – 24 February 1884) was one of the first pioneers of homeopathy in America and remains a widely influential homeopath today.

Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte M.D. (6 October 1811 – 24 February 1884) was one of the first pioneers of homeopathy in America and remains a widely influential homeopath today.

Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte was a colleague of Henry Thomas.

Joseph Hypppolyte Pulte of Cincinnati, Ohio, was born in Meschede, Westphalia, October 6th, 1811. His father, Hermann Joseph Pulte, M. D., was the Medical Director of one of the Government institutions for the education of midwives, and as these had to be organized all over the newly acquired provinces, he was especially deputed for that service, besides presiding over those confided to his care. He was a man of great strength of character, and left a noble example, which his son labored to imitate.

After he had completed his classical course at the Gymnasium of Soest, and his medical studies at the University of Marburg, he accepted an invitation from his oldest brother to accompany him to America.

Eagerly embracing the opportunity thus opened to him, he sailed for the United States in the spring of 1834. Landing at New York, he started for St. Louis to meet his brother who had preceded him, and passing through Pennsylvania, was induced by a personal friend to remain at Cherryville, Northampton county.

Here he formed the acquaintance of Dr. William Wesselhoeft, who, at that time, resided a few miles distant. From him he learned of the system of Hahnemann, and its wonderful success, and on his suggestion was led to test its merits, by actual experiments. The results were so remarkable that he warmly embraced the new system, and became enthusiastic in his devotion to it.

He gave to its study the whole of his energy, and shrank from no hardship or expense necessary to complete acquaintance with it. At that time the labor of attaining a thorough knowledge of homœopathy was very great. There were no books upon the subject to be had. Text-books and repertories were not known.

A large part of the facts and practical knowledge existed only in manuscripts sent from Europe, and here extensively copied and circulated ; these he thoroughly studied.

It was by these means that the first attempt at a more systematic and fixed treatment of Asiatic cholera was transmitted to the Northampton County Society of Homœopathic Physicians, and piously studied and reverentially copied by its members.

Slow and tedious as was this process, it proved effective in keeping alive the zeal of the adherents of the system, and probably made a deeper impression upon their minds. Knowledge thus acquired was not easily forgotten.

Dr. Pulte soon joined the band of homœopathists who had formed the society in Northampton county-the first one of the kind in this country. It registered among its members some of the most eminent practitioners whom the State has ever known, and many clergymen who gave the influence of their position and culture to the advancement of the cause.

The most valuable accession to the Society was Dr. Constantine Hering, who had taken up his residence in Allentown to preside over the Academy which had been formed by the little hand of homœopathists. Dr. Pulte recognized in Dr. Constantine Hering a man of power and of admirable administrative abilities, and submitted gladly to the moulding influence of his genius.

Having assisted to organize the Allentown Academy, he now gave his best energies to sustain its reputation, and advance its prosperity.

After six years of increasing activity, and on the dissolution of the Academy, He went to Cincinnati in 1840, on his way to meet his brother in St. Louis. He traveled in company with an intelligent Englishman, Mr. Edward Giles, who, converted to the theory of homœopathy, needed practical proof if it could be had.

On the steamer he met with the lady who was destined to be his wife [Mary Jane Rollins (1819 – 1889)], and to whom he was married in 1840.

Remaining in Cincinnati long enough to give Mr. Giles an opportunity of witnessing cures by homœopathy, he opened a private dispensary, where soon the sick children of the poorer classes gathered for relief.

It was summer, and the usual complaints of the season were prevalent. Mr. Giles was witness to the marvelous cures performed, and yielded to the force of the evidence thus furnished. The news of his success soon spread over the city, and rich and poor applied to him for help; and, in less than six weeks from the time of his arrival, he was in full practice, and obliged to relinquish his contemplated visit to St. Louis.

In 1846, he published a work on history, entitled Organon of the History of the World. This volume, altogether original in its mode of dealing with its subject, gained for him the esteem and friendship of such men as Alexander von Humboldt, Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Robert Bunsen, Karl Richard Lepsius, and William Cullen Bryant.

In 1848, having originated a plan for carrying the *electric telegraph around the world, via Behring’s Straits, or the Aleutian Islands, to Asia, and thence to Europe, he visited Europe to submit his well matured plans to the governments immediately interested. His efforts were not successful; but the same project, with the same detailed data, are now carried into effect.

While in Europe he did not forget the interests of his beloved science; wherever he tarried in the larger cities he was cordially received by his professional brethren, and he now remembers with delight the social and profitable intercourse he enjoyed with most of the notables of our literature – such as John James Drysdale, John Epps, Joseph Laurie, Frederick Hervey Foster Quin, Paul Wolf, Frantz Hartmann, Gottlieb Heinrich Georg Jahr, and others equally distinguished, and, not least, Madame Hahnemann, the renowned widow of the immortal founder of Homoeopathy).

It was by his exertions and counsel that a uniform prophylactic and curative system was recommended to the Homœopathic Society, and generally adopted by the people.

After this memorable encounter with the most terrible scourge of the world, he had the gratification of seeing homœopathy firmly established in the West and South, and receiving to its fold large numbers of the ablest allopathic practitioners.

In 1850, he published his Domestic Practice, a work that, entirely original in its arrangement, has rendered, by its immense popularity, many works on the subject unnecessary to the present time (which also included directions for the Remedial Use of Water and Gymnastics). Reprinted in London, (with John Epps) it has passed through several editions; and, translated into Spanish, has become the received authority in Spain, Cuba, and the South American Republics.

In 1852, in connection with Dr. H. P. Gatchell [Charles Draper Williams was a co-editor], he commenced the publication of the American Magazine of Homœopathy and Hydropathy. It continued two years as a monthly; in the third as a quarterly, under Dr. Charles Draper Williams, and was then discontinued.

During this time, Dr. Pulte filled with great acceptance the Chair of Clinical Medicine (In 1852 he became Professor of Clinical Practice and Obstetrics) at the Homœopathic College in Cleveland, and afterwards that of Obstetrics.

While lecturing on this latter subject, he prepared for general use a work on the diseases of women, entitled, The Woman’s Medical Guide. It appeared in Cincinnati in 1853. This little work gained a very rapid popularity in this country and in England, and was translated into Spanish in Havana, where it has an extended circulation.

When diphtheria appeared as an epidemic, he embodied in a monograph his views, with the results of his experience, and his mode of treatment. It was widely spread throughout the West.

In 1855, the centenary of Hahnemann‘s birth, he delivered the address before the American Institute of Homœopathy in Buffalo, N. Y.

Full of years and of honors, Dr. Pulte has made the most valuable contribution to the cause of homœopathy in the endowment of the college which bears his name. It was opened in Cincinnati, September 27th, 1872, and is one of the most valuable schools for the advancement of homœopathy.

There is a story told about Joseph Pulte, one of the earliest homeopaths in Cincinnati. When he began his practice, many people were so angered by a homeopath being in town that they pelted the house with eggs. He was becoming discouraged enough to think of leaving.

His wife said, “Joseph, do you believe in the truth of homeopathy?” He replied in the affirmative. “Then,” she said, “you will stay in Cincinnati.” Shortly after, when the Cholera epidemic swept through, Pulte was able to boast of not having lost a single patient– and he was accepted into the community. In the Epidemic of 1849, people crowded to his door and stood in the street because the waiting room was full.

During its prevalence in Cincinnati, in 1849, Dr. Pulte had the satisfaction to see the homoeopathic treatment triumphant beyond any other : through his exertions and counsel, an uniform prophylactic and curative system was recommended to the Homoeopathic Society, and generally adopted and followed by the people, which, under God, saved thousands of lives.

Homoeopathy, after this memorable trial of 1849, was firmly established in the whole West and South, where cities and country received homoeopathic physicians, mostly converts from the old system, by the score, more or less through the agency and influence of Dr. Pulte.

On May 27, 1835 the cornerstone was laid for the main building of the Allentown Homeopathic Academy in a festive ceremony featuring an inaugural address by Dr. Constantine Hering himself.

Two three-story wings of the main building were erected south of Hamilton Street and east of Fourth Street in Allentown; a second building somewhat remote from these was planned to house the chemical laboratory and anatomical and dissecting rooms.

The Pennsylvania State Legislature granted the institution a charter of incorporation on June 16, 1836. Instruction commenced immediately thereafter.

The faculty consisted of Drs. Constantine Hering, William Wesselhoeft, Henry Detweiller, John Eberhard Freitag, John Romig and Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte. Pulte was one of the students at the informal school in Bath. He would go on later to found the Pulte Medical College in Cincinnati, Ohio, and to be named United States ambassador to Austria (and endorsed by Hons, Bellamy John Hudson Storer, Alphonse Taft, A. F. Herr, Carl Shurz, B. Eggleston, W. S. Groesbech and other prominent statesmen)…

… the Homoeopathic Society of Northampton and Adjacent Counties was formed in 1834. The members from Lehigh (at that time Northampton) were Rev. Johannes Helffrich, Dr. John Romig, Dr. Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte and Dr. Adolph Batter. Pulte practiced in Troxlertown…

This society held regular meetings at Bethlehem, Allentown and at the residences of its members. Its object was the advancement of Homoeopathy among the profession, interchange of experience and mutual improvement.

The result of these meetings was the establishment of a homoeopathic school at Allentown, called the “North American Academy of the Homoeopathic Healing Art.”

The Homeopathic Healing Art Plaque in Penn Street Allentown is a bronze plaque on a rock that marks the location of the world’s first medical college exclusively devoted to the practice of homeopathic medicine. Called “The North American Academy of Homeopathic Healing Art,” it was founded on April 10, 1835).

This was the first homoeopathic college in the world. It was founded on the 10th of April, 1835, the eightieth anniversary of the birth of Dr. Hahnemann, the celebrated founder of the homoeopathic system. Dr. Constantine Hering, of Philadelphia, was requested to come to Allentown and take charge of the presidency of the nets college. He accepted the call and became the leading spirit of the new institution.

The Pulte Homeopathic College merged with Cleveland Homeopathic College in 1911 as the Cleveland-Pulte Medical College. In 1914 the institution became the Cleveland Pulte College of Homeopathy, within the medical school of Ohio State Univ. (OSU) in Columbus, OH.

Besides his poetical writings mention should be made of his philosophical work, with which he enriched the literature of the country. It is art attempt to bring revealed religion into harmony with philosophy.

Pulte also contributed to the Transcendentalist journal The Harbinger, published by the Brook Farm community, and he also contributed widely to homeopathic journals.

Pulte continued to be a major figure in homeopathic medicine, having founded, with others, the American Institute of Homeopathy in New York City in 1844. His colleagues included Edward Bayard, Jabez Philander Dake, Walter Williamson, S. S. Guy and Constantine Hering.

Pulte made frequent trips to Europe and Britain in the service of homeopathy.

He died in Cincinnati on 24 February, 1884.

Select Publications:

- Homœopathic Domestic Physician, Containing the Treatment of Diseases: with Popular Explanations of Anatomy, Physiology, Hygiene, and Hydropathy: Also an Abridged Materia Medica. (1851)

- A Homoeopathic Treatise on the Diseases of Children with Alphonse Teste, translated by Emma H. Coté (1857)

- The Household Homoepathist; Or, Mother’s Guide to Practice (1859)

- Letters on Diphtheria with Egbert Guernsey (ca. 1860)

In 1888, as a memorial to her husband, Pulte’s wife, Mary Jane, published a companion to his Homoeopathic Domestic Physician:

Domestic Cookbook: A Companion to Pulte’s Domestic Physician, by Mrs Dr. J. H. Pulte.

Of Interest:

In December 1849, homeopathic doctor Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte of Cincinnati proposed crossing the Atlantic by laying a cable in the opposite direction, a land route via Alaska and Russia, for a total of 18,500 miles from Little Rock, Arkansas, to London, England.

Pulte seems to have been the first to suggest the overland route to Europe, but was unable to interest the US Government in supporting his idea…

It is not known how Pulte became interested in telegraphy, but like other professional men of his time, Pulte probably kept up with the rapid advances in science and technology in mid-century America, the great age of the individual inventor.

In 1848 Pulte visited Europe to submit his telegraph plans to various governments, but received no encouragement. In 1849 he was elected a director of Henry O’Rielly‘s Louisville and New Orleans Telegraph Company, also known as the People’s Telegraph Company, and in December of that year he submitted his plan for the Alaska-Russia route to the Congress of the United States.

Until Cyrus West Field came along in 1854 no-one wanted to spend his own money on intercontinental telegraphy, so as Horatio Hubbell had done, Pulte presented a memorial to Congress in the hope of public funding, and as with that of Hubbell, Pulte’s memorial got no further than referral to the Committee on Commerce.

There it was ordered printed as Senate Miscellaneous Document 109 and laid on the table, no further action being taken. The full text of Pulte’s memorial is shown below.

Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, Friday, March 15, 1850. A plan for extending the magnetic telegraph around the globe. (Presented to Congress by Salmon P. Chase)

March 15, 1850. Referred to the Committee on Commerce. April 23, 1850, Discharged, ordered to lie on the table, and be printed.

To the Senate of the United States: Your memorialist would respectfully represent: Not twenty years have yet elapsed since the discovery was first made of using electricity for telegraphic purposes; and it is not ten years since it was first practically tested in the United States, by Professor Morse between Washington and Baltimore; and already we see this immense country, from north to south, spun over by the wires of the electric telegraph, everywhere diffusing its innumerable blessings.

Its general usefulness and practicability have been thoroughly tested, and the importance of its services is felt immediately when an accident only for twenty-four hours has interrupted its workings.

So deeply has this wonderful telegraphic system penetrated into the very organism of our nation, that we henceforth cannot live or move without it.

More than ever do we feel ourselves as one united people, its one body, whose soul is everywhere present at the same time, in will and sentiment, although spread over so vast a space.

In contemplating these wondrous results, by such small and comparatively insignificant means, the American citizen feels a just pride to know that to the genius of his own country is due the perfection of the mode of telegraphing; that his Congress generously offered the first aid in testing its practicability at a time when scoffers and incredulous persons were not wanting to throw ridicule and sarcasm in the way of its progress.

But thanks to the American character, which is not so easily deterred from great enterprises by sneers and ridicule! Time – memorable experience – has shown him too well the greatness of his own destiny, and, consequently, the importance of those arts which, invented for his own country, have had, nevertheless, a bearing upon all the civilized nations of the earth.

The sneers and ridicule of monarchical Europe could not prevent the early fathers of this glorious Union from testing the practicability of self government; and, behold! monarchies vanish daily away, and those which remain try to hide their intentions behind constitutional cloaks.

Instead of ridicule on account of his political institutions, the American now meets everywhere admiration. A nation to whom such an exalted station was given, and which has so far proved to be true to its course of greatness in every respect, is not likely now to shrink from fulfilling those destinies which are commencing to show themselves in all their future splendor and importance.

There is no reason to doubt that, large as this country is, the day will not be far distant when the telegraph system will be in successful operation as far as California and Oregon – when one touch of the finger will send the greetings of the Atlantic, in a moment, to the Pacific. Then this nation will have performed a noble task!

But a still nobler one awaits it; and, although the time of its completion may not yet have arrived, it is well enough to lay the foundation immediately.

This great work, yet to be accomplished, is the union of civilized Europe with our own country by the electric telegraph.

To this grand undertaking many minds in the United States have of late simultaneously turned their attention – some in a mood of fancy and sport, others with earnest and decided intentions to bring about its accomplishment.

Your memorialist likewise made, several years ago, such preparations as were within reach of a private individual, and undertook personally, during the summer of 1848, to bring this subject to the knowledge of influential persons in England and on the continent of Europe, in order to create at least sympathies for this great work.

Though the disturbed political state of Europe prevented for a time any practical results, my plan met with the approbation of persons who have long been and are yet held in the highest respect in both hemispheres, and who will give their powerful aid for its completion when they are called upon to do so.

To reach London telegraphically by way of the Atlantic, is clearly impossible. It is unnecessary to enumerate here all the impediments in the way of accomplishing it.

The only course left to us is by way of Oregon, Behring’s straits, Moscow, and Petersburgh; and I will try to show, in the following, the possibility and practical workings of this route.

I do not deny that there are great difficulties to be overcome – some of them seemingly insurmountable. But, if we consider again the object to be reached, the benefits to be gained for individuals, nations, and mankind in general – particularly, however, for physical science – we must try to surmount any obstacle in our way, calling all our energy and judicious management to our help.

This grand enterprise derives, moreover, a peculiar importance from the geographical position of the United States and Russia, the two nations most interested in its completion and successful operation, in as far as this telegraph is to run almost exclusively through their territories, which girdle three-fourths of the northern hemisphere.

Russia and the United States, antagonistic as they may be in internal politics, are, more than any two contiguous nations, remote from altercations and international difficulties, neither being afraid of the other’s growth and prosperity.

This undoubted fact outweigh hundreds of difficulties which may impede the construction of this telegraph, as thereby its permanency for the future is safer, and more beyond the reach of mere political events, than a telegraph line from Vienna to Perth, or from Paris to Rome.

If once constructed, it never would have to fear any other interruptions than those from physical causes, which can be more easily controlled than those occasioned by political events.

The small interest which England has in the north Pacific, on account of its possessions in Oregon, is not sufficient to disturb at any future time the workings of the telegraph through that Territory, as the representation of the United States and Russia in that quarter of the globe is too powerful to be resisted.

Moreover, it ought, above all, to be the duty of the statesmen who will have to create this telegraph diplomatically to save it from destruction in time of war, by declaring it sacred before the political tribunals of the world.

Suppose this telegraph should commence at Little Rock, in Arkansas, or at Independence, in Missouri, (the distances from either place to Santa Fe varying not much:)

Then we have from Little Rock to Santa Fe 800 miles.From Santa Fe to San Francisco 1,000 miles. From San Francisco to Astoria 1,000″ Total 2,800″Or 3,000 miles of telegraph, which we would have to erect within our own territory.

This would be a short distance in comparison with that in the Russian and English territories, as the following numbers will show: From Vancouver’s island, on the Columbia river, to

Behring’s straits, over Sitka, Prince William’s sound, across to Norton’s sound, and thence to the cape of Prince of Wales 2,000 miles.From Behring’s straits to Ochotsk, on the like-named sea 1,800″ From thence to Yakutsk, in the land of the Yakuti 800″From thence to Irkoutsk, on the Chinese frontier 1,200″ From thence to Tobolsk, in the heart of Siberia 1,800″

From thence to Moscow 2,500″ From thence to St. Petersburgh 500″ Total 10,600″

More than three times as much as we would have to construct. In addition to the above 10,600 miles, Russia would have 400 miles of telegraph to erect from St. Petersburgh to the Prussian frontier, swelling its own line to 11,000 miles, while our line would hardly come-to 6,000 miles, even if we counted from the Atlantic to Independence, in Missouri, 3,000 miles, as already completed.

Prussia has the telegraph complete through the whole breadth of its territory to the extent of 900 miles, and there is very little wanting to make its connexion with Paris complete, which would be 300 miles in addition.

From Paris to London would he between 200 and 300 miles. The whole length of the telegraph around the world would be, therefore, about 18,500 miles – a route which, as it sweeps around the globe, visits all those countries where the dearest interests of mankind and their civilization are stored up, bringing them all in immediate contact, extending itself from Atlantic to Atlantic, as the great river of thought, into which may flow from all sides the smaller streams of all the nations of the earth.

From Irkoutsk, on the Chinese frontier, a branch line may dive into Chinese Tartary, to connect Pekin, Nankin, Canton, and Calcutta, opening the Celestial Empire more and more, and bringing the affairs of the East India empire, within an hour’s time, under the eyes of the home government.

From Moscow a branch line might run to Odessa, on the Black sea, and from thence to Constantinople and Athens, facilitating the trade and advancing the interests of civilization in the Orient and its dependencies.

We leave now to every one to complete this list of branches to the principal line, as he very easily can do by looking at a map, where he will be obliged to draw yet innumerable branch lines, if he has any faith at all in the progress of civilization.

It is, however, all-important to consider well that this route across Behring’s straits will be the main channel of all the telegraphic systems of the world, as our country will be the main thoroughfare between China and Eastern Asia and Europe, as soon as the proposed facilities for transportation across the isthmus of Panama, or a great central railroad to the Pacific, are completed.

Our own interests as a nation are deeply interwoven with this enterprise, and not the less so since California has risen to such an importance in our financial affairs.

As a nation, we cannot engage in a greater and nobler work.

There is no monument existing of a nation’s greatness which can be at all compared with a telegraph of 20,000 miles in length.

Such a work is more worthy to call into action the energy of a whole nation than all the schemes of conquest which way be laid before her, ever so enticing.

Let us choose the nobler pursuit, which civilizes and purifies. The time to make a commencement has now come. The nations of Europe, more now than ever, have seen the folly of gaining laurels in fruitless efforts of lording one over the other; and they will, perhaps, more than ever, be willing to co-operate with us in this grand undertaking, heralding the flashes of lightning from our shores to their distant homes as so many friends of liberty and peace.

In constructing this telegraph, we would not meet with so many difficulties within the American territory as when its course enters upon Russian soil. From western Missouri to San Francisco, over the prairies and through the mountain passes, the construction of the line is possible beyond a doubt, as the greatest impediment in these regions only would be the scarcity of timber – a difficulty which capital and perseverance could overcome.

From San Francisco to Oregon and the British possessions, the country presents greater facilities to construct the line, for the reason of having the material near, and the road easy of access, as it will have to run along the coast of the Pacific.

Vancouver’s island, as a central depot for the steamers engaged in this work, has plenty of coal to provide these and the different stations with fuel.

Up to this point, the climate of the country does not yet prevent the possibility of constructing the line, or keeping persons on the stations during the whole year. In the British possessions, the climate is yet temperate, and the soil productive and fertile.

But further north the difficulties in this respect increase rapidly. Yet even here the footsteps of man are not wanting, and civilization has commenced to diffuse its blessings.

The Russian possessions, facing the coast for hundreds of miles, contain some of the most important points of the fur trade carried on by the Russo-American company.

New Archangel and Sitka are already places of considerable importance; and further north the company have a great many posts or stations, where their servants stay during the whole year, without being driven away by the severity of climate or unproductiveness of soil.

Our age has, indeed, the means to make the most inhospitable corner of the globe comfortable as regards living and enduring, if important objects shall be gained.

Sir George Simpson, who visited these northern settlements in 1842, speaks of them as follows:

“On the 4th of May the Ochotsk sailed for Oonalaska and some other neighboring stations. She had the good bishop as a passenger for her first-mentioned destination, whence the Bichal was to convey him to Kamtschatka.

She was also carrying Lieutenant Fagoiskin to Norton’s sound, who was thence to explore the interior as far as Bristol bay on the one side, and on the other to examine the Quahpark – a large river falling into Behring’s straits.

The object of this expedition was to occupy the country by posts, in order to protect the trade from the Schuktchi of Siberia, (by no means a savage tribe,) who cross the straits every summer to traffic with the American Indians, carrying their furs, ivory, &c., to the fair of Ostroonoze, situated on the Lesser Aning, on the Asiatic side of the straits.

At some points Behring’s straits are only 45 miles in width, with a chain of islands, like so many steppingstones, extending from shore to shore-the longest traverse not being more than seven miles; so that the navigation is practicable even for small canoes.

In the general appearance of the two coasts there is a marked difference – the western (or Asiatic) side being low, flat, and sterile, while the eastern (or American) is well wooded, and in every respect better adapted than the other for the sustenance both of man and beast.

Moreover, the soil and climate improve rapidly on the American shore as one descends; and, at Cook’s inlet, potatoes may be raised with ease, though they hardly ripen in any part of Kamtschatka, which extends nearly ten degrees further to the south.

As, in addition to the advantages of cultivation, deer, fish, game, and hay are abundant, the company contemplates the forming of a settlement here for the reception of its old servants.

In the neighborhood, on an island near Kodiak, there is plenty of good coal, used both for the hearth and for the forge, though it is objectionable for the latter purpose, as producing too great a quantity of ashes.”

In the following pages, Sir George Simpson describes the aborigines of this part of the American coast as being on the friendliest terms with the Russo-American Company. He says, further:

“The Kaluscians are a numerous tribe, their language being spoken all the way to the northward from Stikine as far as Admiralty bay, rear Mount St. Elias; thence to Prince William’s sound is another language; and four or five more languages divide between them the coast up to Icy cape, north of Behring’s straits.”

He remarks further, speaking about the Russian stations,

“New Archangel, notwithstanding its isolated position, is a very gay place.”

Speaking about the Aleutian Archipelagoes, he says, page 99:

“The soil and climate of some of the more easterly islands of the Aleutian Archipelagoes are sufficiently good for the production of potatoes and the maintenance of domestic cattle, while at Kodiak there are also gardens for vegetables.

On this last-mentioned island, which possesses a tolerable surface of pulverized lava and vegetable mould, there exists a village of about four hundred inhabitants, the oldest settlement to the north of California.

The Russians are certainly entitled to the credit of having been the first to plant civilization on the northwest coast.”

From the above statements of a traveller, who describes these northern regions from personal observation, we can gather at least thus much: that the rigor of climate and sterile condition of the country are not such as to drive human beings entirely from its shores.

Not only do numerous tribes of Indians inhabit the country up to Behring’s straits, and even further north, up to Icy cape, but a trade in furs and ivory is carried on between the Schuktchi on the Asiatic, and the Indians on the American side of Behring’s straits, and a fair is held in the same degree of latitude on the Asiatic side.

All these are unquestionable signs that people can live, and, to their notions, comfortably, in these regions.

It is to be presumed that their conditions of life would rather improve than otherwise, and with it the hospitable character of the country in general, if an establishment like the telegraph would sweep through these wildernesses, accompanied with all the necessities of civilized life, bringing along the artisan and missionary.

The account of Sir George Simpson speaks of the American side of Behring’s straits as being well wooded – a sign that vegetation is not altogether at an end there – lessening the cost of erecting the posts and stations considerably; besides, there is plenty of coal near the island of Kodiak, from which point all the stations north of it, on the straits itself and in the interior, on the Asiatic side, would be supplied with coal, as far down as Ochotsk itself, where Siberia proper commences, with a civilization and climate sufficient to overcome all further difficulties in the erection of the telegraph through to Europe comparatively easily.

In crossing Behring’s straits, the wires would have to be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, which is here very shallow, thirty fathoms being the greatest depth; and as the greatest distance from island to island is only seven miles, the sinking of the wires would be easily accomplished, in comparison with the intended sinking of wires between Dover and Calais, where the straits are twenty-one miles wide and the ocean deeper.

Another important consideration has been, to find out the probable cost of this stupendous undertaking, in order to show its capability for rewarding, in rich revenues, the financial outlay.

The telegraphs of this country have been constructed, generally, at an expense of one hundred and fifty dollars per mile, and fifty dollars for every additional wire stretched.

Now, allowing four times that amount per mile, (as the expense of erecting the telegraph on the prairies will be greater,) the cost for the three thousand miles to Oregon would be, for a telegraph with two wires, two and a half millions of dollars, including one hundred thousand dollars for the necessary instruments.

If, every forty miles, stations are erected, their number would amount to seventy-five – the erection of which would not cost more than one million of dollars.

The total outlay of capital for the three thousand miles of telegraph would, therefore, not exceed three and a half millions of dollars.

The yearly expenditures would be as follows: Interest, at six per cent., on three and a half millions $210,000

Support and salary of six hundred persons at the seventy-five stations, at one thousand dollars each per year 600,000

Wear and tear of instruments, &c. 100,000 $910,000

Probable income of this line, per year, $1,000,000; leaving a surplus in its favor of $90,000 per year.

If this telegraph is once constructed, under such favorable financial prospects, it is not probable that the above figures would change unfavorably during a ten-years duration; at least, the established lines have shown a decided increase of income over that of former years, even in towns where rival lines existed.

And, as California and Oregon rise in importance as regards population and business, the telegraph will increase in revenue in the same ratio.

The above view of the finances of the telegraph is taken without any regard to its final extension to Asia and Europe, or branches to Mexico and South America, which would swell its income still higher.

These calculations place the telegraph around the world in the rank of sound speculation, and leave no doubt of its ultimate completion.

As works, however, of such magnitude require time and well-matured plans, and, as in this case, diplomatic arrangements with various nations have to be entered upon, the prayer of your memorialist limits itself to the following:

1st. To a resolution in favor of the above project.

2d. To the adopting of means for carrying out the preliminaries for its final successful completion – such as exploring the routes, as far as Behring’s straits, in relation to this object, and then, in the same time, conferring diplomatically with the several governments whose territories the proposed telegraph would have to traverse, for the purpose of uniting their several efforts in carrying it successfully around the globe.

All of which is respectfully submitted. J.H. PULTE. CINCINNATI, December 1, 1849.

Leave A Comment