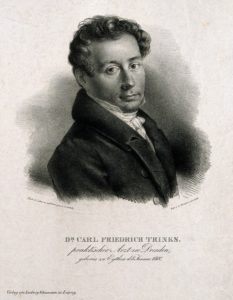

Karl Friedrich Gottfried Trinks M.D. Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Karl Friedrich Gottfried Trinks M.D. (8 January 1800 – 15 June 1868) was a German Jewish physician who practiced in Dresden, and he was a student of Samuel Hahnemann.

In 1848, Trinks met Charles II Duke of Parma who awarded him a Knightship of the Lucchesischen Order, Trinks treated Maximilian II of Bavaria, he became the Medical Counsellor to Ernest II Duke of Saxe Coburg and Gotha, and in 1863, John of Saxony awarded him a Knightship of the Royal Order of Albrecht.

Trinks was a colleague of Clemens Maria Franz Baron von Boenninghausen, Ernst von Brunnow, Carl Franz, Philip Wilhelm Ludwig Greisselich, Carl Georg Christian Hartlaub, Frantz Hartmann, Christian Gottlob Hornburg, Christian Freidrich Langhamme, Georg August Heinrich Muhlenbein, Alphonse Noack, Rodolphe Noack Paul Wolf and many others.

Trinks was a member of the Board of Directors at the Leipsig Hospital alongside Georg August Benjamin Schweikert, John Ernst Stapf, Gustav Wilhelm Gross, Friedrich Jakob Rummel, Hartlandson, Georg August Heinrich Muhlenbein, Raehl, Paul Wolf, and of the Leipsig physicians, Frantz Hartmann, Carl Haubold, and J. A. Schubert.

The following biography was written by the old friend of Dr Trinks, Bernhardt Hirschel, soon after his death. It was translated by Walter H. Dunn of Cambridge, England, and published in the Monthly Homeopathic Review Vol. XIII., p. 122.

Under his direction Trinks made his first acquaintance with Latin and French, with history, mathematics and some branches of natural science. With Greek he scraped an acquaintance with no other aid than that of a Greek grammar.

In 1814 he was removed to the Grammar School of Merseburg. Here he worked hard, his industry being rewarded by the love of his teachers and the generosity of his uncle, through whose liberality he was enabled to devote himself to the study of medicine. Unhappily his uncle died shortly after his entrance at the University of Leipsig. With his death his means of living became greatly straitened. His mother having always opposed his desire to become a physician, in the hope of turning him to more profitable account as a miller, limited his allowance to some six shillings a week.

Trinks was in earnest, and a poor dinner never yet stood between the man who is really in earnest in the acquirement of learning and the accomplishment of his design. What Trinks wanted in money he made up for in energy.

Before going to Leipzig the surgeon of his native village, Bodentein by name, had given him some instruction in the elementary parts of practical surgery. With this gentleman, who removed to Leipzig, he resided during his career at the University, which commenced at Easter, 1817, by his being enrolled a pupil of Beck, a well known physiologist of that day. He remained at the University until July, 1823, taking his degree of doctor of medicine in the September following. The title of the thesis defended by him on this occasion was as follows: De primariis quibusdam in medicamentorum viribus recte aestimandis dijudicandisque impedimentis ac difficultatibus.

In this essay the author displayed that love of therapeutics which he never ceased to feel during the whole of his career, and to his intimate acquaintance with which may be traced his success as a practical physician.

In this youthful production he displayed, in correct and classical Latin, the sources of error in acquiring a knowledge of remedies which have arisen through theoretical speculation and fallacious experiments.

He pointed out the difficulties surrounding the prescription of medicines caused by variations in the susceptibility and power of reaction of the organism, those presented by age, sex, constitution, mode of life, and by the combination of drugs in estimating aright the nature of medicinal action.

The influence of the homeopathic school upon him is here observable in his desire for experiment, for obtaining the specific and dynamic action of drugs, and in the need he sees for a simple arrangement of remedies. Previously to the time when this thesis was defended he had been acquainted with some of Samuel Hahnemann‘s colleagues, with Carl Franz and Christian Gottlob Hornburg, and subsequently with Frantz Hartmann, Christian Freidrich Langhammer and others.

No one, however, had greater influence over the young student than Carl Georg Christian Hartlaub, senior, who earnestly directed him to the new therapeutic light, their mutual interest in which formed a bond of union and enduring friendship.

Samuel Hahnemann, whom he frequently saw on the promenade at Leipsic, he visited first at Coethen in 1825, again in 1832, and once, subsequently, with Councillor Paul Wolf.

In 1824 Trinks settled in Dresden. He and Ernst von Brunnow were the earliest homeopathists there. (Though G Severin treated Marie Henri Beyle, Stendhal in Berlin in 1821, shortly before he too moved to Dresden).

His intellectual clearness, his critical acumen and ability as a physician soon gave him that prominent position required for the success of the new school, to the development of which he devoted an energy and a zeal which could not brook imperfection in anything towards which they were directed.

Notwithstanding his increasing professional engagements he felt dull and lonely in Dresden and removed to Bremen, only, however, to return to Dresden at the end of the year 1826. His practice and reputation spread rapidly and provoked the enmity of his Allopathic neighbors so far as to lead to his being summoned before the magistrates on the charge of dispensing his own medicines, a practice prohibited in Germany, but long since permitted to homeopathic physicians.

In December, 1827, he married.

In 1830 Trinks attended the first meeting of homeopathic physicians held at Leipsic, and assisted at the foundation of the Central Society of German Homeopathic Physicians.

In 1832 he made the acquaintance of Philip Wilhelm Ludwig Greisselich, whose views, coinciding with his own, induced him to contribute largely to the Hygea.

The only volume of importance published by him was that in which he was a joint author with Alphonse Noack – the well known Alphonse Noack and Trinks’ Handbook of Materia Medica; but the essays he has contributed to the periodical literature of homeopathic medicine are numerous.

The two diseases in the study of which he felt most interest were typhus fever and cholera. On the former he was engaged in the preparation of a monograph at the time of his death. In August, 1867, at a meeting of the Central Society, he excited the admiration of the members present by his excellent, albeit extemporary, address on cholera.

In person Trinks was tall and stately; his head handsome and well developed; his blue eyes expressed the earnestness and power of penetration which marked his character; while the roseate hue of his cheeks gave the old man quite a youthful freshness of countenance which he never lost to the last. Intellectually he was clear, keen, and critical to a fault.

It was in polemical rather than in original oratory that he excelled. He was an eminently practical man with but little poetical taste. He possessed a well stored and a wonderfully retentive memory. This preference for fact over theory, his love for the real rather than the ideal, contributed largely to make Trinks what he was, a thorough physician.

Homeopathy he loved, because in its school alone did he meet with that full development of the principle of pure observation he felt to he so necessary for the practice of medicine.

A thoroughly independent thinker, it was not long before he found himself somewhat opposed to Samuel Hahnemann ; and on one occasion he had a warns discussion with Clemens Maria Franz Baron von Boenninghausen, when he endeavored to introduce mixed medicines into the practice of homeopathy.

He most earnestly opposed everything in the shape of mysticism, everything having the aspect of humbug with which it was sought to connect homeopathy. On these grounds he declared himself an enemy of the so called high potencies and a supporter of the lower dilutions.

Trinks’ manner to one seeing him for the first time was often blunt and even somewhat repulsive. In diagnosis and prognosis a want of caution in communicating his apprehensions to patients was often remarked in him. His dietetic rules for those under his care were very rigid, his prescriptions, carefully selected, were adhered to with a tenacity which, though often regarded as unwise by those around him, was generally rewarded by satisfactory results.

Books afforded him the only recreation from professional duty he cared to enjoy. His habits were of the simplest, and their being so doubtless conduced materially to maintain that degree of sound health which during forty four years of arduous professional labors knew not the interruption of a single day.

His reputation as a physician, and his services to persons of high rank, met with suitable acknowledgment in his decoration with several royal orders and his advancement to the position of Medical Councillor. Throughout the North of Germany Trinks was regarded as the most distinguished physician who had practiced homeopathy since the time of Samuel Hahnemann.

His sound and varied learning, his thoroughly critical character, the care he bestowed upon his patients, and the success which attended his treatment of disease, together with his important and valuable contributions to medical literature, rendered him much sought after by patients, and his opinion highly esteemed by his medical brethren.

He died at Dresden on, the 15 th of July, 1868, after an illness attended with much suffering. His widow, a son holding a judicial position in Leipsic, and a daughter, the wife of a military officer, survive him.

Dr. Trinks died at Dresden. June 15, 1868, at the age of sixty nine years.

(British Journal of Homeopathy Vol. XXVI, p. 693.) Samuel Hahnemann, whom he frequently saw on the promenade at Leipsic, he visited first at Coethen in 1825, again in 1832, and once, subsequently, with Councillor Paul Wolf.

Select Publications:

Leave A Comment