Mary Jane Hall-Williams M.D. (22 June 1845 – 22 January 1932) was the first qualified woman homeopathic physician to practice in the United Kingdom. In 1880, Hall graduated M.D. from the homeopathic Boston University School of Medicine. She subsequently practiced medicine in London and Cornwall.

Mary Jane Hall-Williams M.D. (22 June 1845 – 22 January 1932) was the first qualified woman homeopathic physician to practice in the United Kingdom. In 1880, Hall graduated M.D. from the homeopathic Boston University School of Medicine. She subsequently practiced medicine in London and Cornwall.

Mary Jane Hall was born in Liverpool, England in June 1845, one of four children of Quaker and grocer John Hall and his wife Hannah.

[note: William Harvey King in his History of Homoeopathy and Its Institutions in America identified her birthplace as Liberty, Kansas].

Hall’s early life is unclear but in 1880 she graduated M.D. from Boston University Medical School.

Hall was one of the attendees at the second quinquennial International Homeopathic Convention held in London in July 1881. At the time she was listed as practicing in Boston, Mass.

Hall was a friend of lay homeopath and women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton who, after visiting the U.K. in November 1882, noted that her friend “Dr. Mary J. Hall was the only woman practicing homeopathy in England.” Hall was a dedicated suffragist and was listed as one two thousand British women signatories demanding the franchise in 1889, alongside other notable medical women including Elizabeth Blackwell and Sophia Jex-Blake.

In 1890, aged 45, Hall married mechanical engineer Francis Vyvyan Williams (1849 – 1922) of Helston, Cornwall.

Hall-Williams continued to maintain property in London, at 10 Phillimore Terrace, Kensington. On Thursday April 30, 1891, she had opened up her drawing rooms there for a meeting of the newly founded Friends’ Anti-Vivisection Association, chaired by the Theosophist and author Edward Maitland.

As with many homeopaths, Hall-Williams was an active opponent of vivisection. She gave a number of public lectures on the topic, including a paper entitled “The Uselessness of Vivisection” to a large audience in Perth, Scotland, in December, 1893, one entitled “Vivisection – is it Justifiable?” in Dublin at the Friends’ Institute in February 1894, and another paper, “Vivisection, What is It?” to The Scottish Society in Glasgow in December 1894.

In June 1895, Hall-Williams and her husband were both in attendance at the twentieth annual meeting of the Victoria Street Society (later renamed the National Anti-Vivisection Society), held at St. Martin’s Town Hall, Charing Cross, London. One of the guest speakers on the platform was homeopath Dr. John Henry Clarke.

Hall was a colleague of many leading British homeopaths, including, Edward Berridge, James Compton Burnett and Robert Thomas Cooper. In August, 1896, she attended the Fifth Quinquennial International Homoeopathic Congress held in London.

In 1897, the now Mary Jane Hall-Williams, penned a short 10-page pamphlet, Ovariotomy Averted, in which she argued against the surgical removal of ovaries in favour of more humane and rational methods of treating ovarian issues.

In November, 1898, Hall-Williams re-launched the Penzance Homeopathic Dispensary, originally established in February 1858, at 26 Clarence Street. However, Hall’s medical diploma from an American homeopathic institution meant that she was not eligible to be added to the UK medical register. This provided the editors of the British Medical Journal with a justification to canvas for the prohibition of Hall’s Penzance Dispensary.

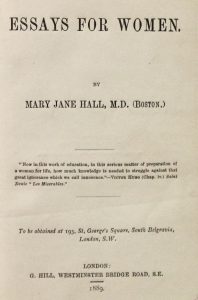

The final chapter of her 1899 book, Essays for Women, was devoted to homeopathy.

Hall occasionally contributed to the homeopathic literature. Her commitment to homeopathic therapeutics, and her abhorrence of animal vivisection, were both foregrounded in an essay published in 1905 by the Cincinnati Medical Advance titled “Hope for Cancer.” In this essay, Hall revealed that a vegetarian diet was optimal for good health.

In September 1905, Mary Jane Hall Williams was convicted in Helston, Cornwall of failing to notify the district medical officer of “an alleged case of typhus fever,” despite her signing the death certificate accordingly. She was ordered to pay costs of £1 and 12 s. 6d and henceforth the town required all death certificates signed by unregistered persons be referred to the coroner. The incident, reported in the British Medical Journal, was particularly tragic in that the deceased was her sister in law, Margaret Williams, who had fallen sick at a picnic on 11 August 1905 and she died eleven days later. Hall-Williams had diagnosed typhus fever, although the court emphasized that this diagnosis was not corroborated.

Hall-Williams relocated permanently to Penzance by April 1913, owing to her husband’s ill-health.

Mary Jane Hall-Williams died at home, 12 Penrose Terrace, Penzance, on 22 January 1932.

Select Publications:

- Essays For Women (1889)

- From the Human and Scientific Standpoint (1895)

- Ovariotomy Averted (1897)

Leave A Comment